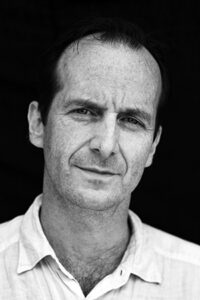

Before he was a familiar face in numerous films and TV shows (American Horror Story, The Good Wife, Charlie Wilson’s War, The Proposal), Denis O’Hare was a venerable stage actor with scores of credits across Broadway, Off-Broadway, and the West End. Returning to his tour-de-force performance in An Iliad at Spoleto, O’Hare talks to Spoleto’s Chief Marketing & Communications Officer, Katharine Laidlaw, about his Tony-winning turn in Take Me Out, being recognized all over the world, and why Homer’s Iliad still resonates.

Katharine Laidlaw: How did you discover your passion for theater?

Denis O’Hare: I was a musician first. My mom was a church organist, my uncle was a violinist for the Detroit Symphony, my aunt was a cellist, and my cousin was a pianist—so I was raised with music. I started playing organ at five and played church organ in high school for a parish. And they fired me because I didn’t have enough authority (laughs). My first community theater experiences included Showboat and Carousel, and then all through high school I did musicals: Once Upon a Mattress, Man of La Mancha, Jesus Christ Superstar. Somewhere around 16, I went to a summer program at Cranbrook, which is a famous school in Michigan, and I was exposed to straight acting. Kind of a watered-down version of Stanislavski: Who is your character? What’s his background? It blew my mind and I became a total convert. I enrolled at Northwestern University in the theater program.

KL: Which roles do you remember most fondly and why?

DO: I did a play years ago called, The Devils by Liz Egloff, at New York Theatre Workshop, directed by Garland Wright, who was dying at the time. The cast was full of wonderful actors: Bill Camp, Kali Rocha, Randy Danson, and Boris McGiver. The play, however, was 3.5 hours long and everybody, including critics, hated it. I played a thoroughly unlikable, unpleasant character—I had a speech at the end where the audience would flee. But it was a great actors’ piece. There were 16 of us crammed backstage, but I just loved that downtown theater experience.

I also was in a dance-theater piece with Martha Clarke called Vienna Lusthaus, working with some really wacky downtown theater people. Because she came from the dance world, Martha didn’t know how to direct actors at all. It was a very strange production, but it was so much fun and just a beautiful work.

KL: You’re a prolific character actor with scores of television and film credits. I expect you get recognized quite a bit as “that guy.” Tell me memorable stories of people recognizing you.

DO: Just recently, I was in Athens, Greece, and when I arrived at my hotel, the guy at the front desk said “Welcome back!” I get this a lot, but it was my first time in the hotel. So, I replied, “No, this my first time here.” He responded: “No. No, you come.” And I said, “No. First time here.” We went back and forth until finally I said, “I’m an actor.” And then he backpedaled.

Another time, I was in Egypt touring the Valley of the Kings, and a woman in a full burqa points in my direction. I heard this voice coming out from behind her veil, and she was saying “Mr. Gilbertson. Mr. GILBERTSON!” I had no idea who she was talking about because I forget my character’s names. Mr. Gilbertson was my character’s name in The Proposal. She was so overwhelmed by meeting Mr. Gilbertson and wanted to take a selfie with me. Here she was, touring the Valley of the Kings, but wanted a selfie with me! And I thought wow, the long reach of American export of cinema and TV. I was with Phillip Seymour Hoffman filming a movie called Charlie Wilson’s War. And this 17-year-old Moroccan kid stopped us and reeled off 15 of his films in an incredibly good American accent.

KL: Yes, and what it says about the United States’ cultural cachet, and “soft” power. And yet our government doesn’t subsidize film or the arts the way many our countries do.

DO: It’s frustrating, because when we’ve toured An Iliad to places like New Zealand, Australia, Romania, China, Chile, we have not been supported by the US government. We got some modest funding when we performed at the embassy in Cairo for a benefit. And we were happy to do that. So we asked, How can we continue this? We’ll take whatever you can give us. It’s helpful…but we don’t make money on this. There’s no centralized office where you can go to the State Department and tell them that we are a valuable cultural asset. We are happy to represent America—use us, fly us over there, and we’ll do wonders for you. But, no.

KL: We have to talk about your Tony-winning role in Take Me Out, which also won the Tony for Best Play in 2003 (and the revival won another Tony last year). It was a groundbreaking work. Did you know then that you were part of something that would change the way people thought?

DO: Early in the experience I kept thinking my character was going to get cut, because the play is about a baseball player and I was a sideshow. What I did not realize—and what that the play’s success makes evident—is that the character Mason is the heart and soul of the love of baseball. He is the fan, and the fans are what make it. He’s the theatergoer sitting in the audience just kvelling over the thing. That’s the fandom that [the playwright] Richard Greenberg was talking about in Take Me Out, as well as politics and sexual politics. It’s the love of sport. After Take Me Out, so many people have asked if I love baseball. And I tell them no, I find it boring. But I am an opera fan. The way Mason, my character, feels about baseball—that’s how I feel about opera. When opera works—you know, when the costumes and the lights and the music and the voice and the story and the words meet—it’s more powerful than anything else in the world. It’s nuclear. But back to the question, I loved, loved the experience of Take Me Out, but none of us thought it was going to be what it was.

KL: For someone who has not read (or thought about) The Iliad since high school, what are the Denis O’Hare Cliffs Notes? What are some key plot points or themes that emerge?

DO: The Cliffs Notes version, I suppose, is that the most beautiful woman, Helen [of Sparta], has been stolen by Paris [Prince of Troy] from her husband, Menelaus. His brother, Agamemnon, is the powerful leader of the Greek nation states. And he and all the other Greek leaders who were suitors of Helen made a pact to defend Menelaus when he was picked to be Helen’s husband.

An Iliad, photo by Joan Marcus

KL: An early form of NATO when you think about it.

DO: Right? But the [the Greek hero] Achilles has no dog in this fight. He is not part of the pact. He comes for honor and glory. I mean, the funny thing about The Iliad is that it’s the Trojan War. Everybody knows that the Trojans lose when the wooden horse is wheeled into the city and the Greeks come out and kill them. And everybody also knows that Achilles dies because of his heel. But none of those events occur in The Iliad. Those are in The Odyssey. The Iliad takes place over just nine days in a nine-year war. It’s an extraordinarily compact, telescopic story. And it begins at a pivotal moment when Achilles has a massive tantrum and refuses to fight. And because he refuses to fight, the Greeks start losing. And because they start losing, Achilles’s companion, Patroclus, is killed. So then, Achilles gets back in the war, and he kills Hector [Paris’s brother and heir to the Trojan throne]. So there’s a funeral, during which there’s a nine-day pause.

The simple throughline is rage. The very first word of The Iliad is rage: Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’s son Achilles—murderous, doomed. And the very climax of the work is when Priam [King of Troy] comes to ask for his son’s body back. And in that conversation, he ignites something in Achilles who becomes enraged, but manages to claw it back and be kind to Priam. He finds a moment of grace. So that is the remarkable arc. Achilles learns to master his rage, and he says to his mother at one point, “if only anger would die from the hearts of gods and men. If only we could get rid of this.” He wishes his rage would go away. That, to me, makes Achilles a beautiful character.

KO: What drew you and co-writer/director Lisa Peterson to The Iliad, and what made you decide to adapt it as a vehicle for a one-person performance?

DeO: This is definitely from the mind of Lisa Peterson. She approached me some 20 years ago and asked if I was interested in reading The Iliad with her. Years earlier, she had seen a one-man reading of The Gospel of Saint Mark and was so compelled with this notion of a single person engaging with a classical text. And because we were at war—we had just invaded Iraq—she wanted to do a play about war. She looked around the world and thought, Where are the plays being written about what we’re doing? Why is nobody writing about what’s happening?

Lisa and I adapted The Iliad from two very specific viewpoints. Mine was that war is a waste. Lisa’s was that men are always trying to kill each other. Yet the meta-theme of our play is storytelling. I play a man who’s compelled to tell a story that he doesn’t want to tell. Why is he telling it? What does he hope to achieve? And at the end of the evening, has he achieved anything?

KL: You wrote this play many years ago, and yet it’s not only relevant, but prescient, especially considering the invasion of Ukraine by Russia.

DO: You know, we keep waiting for the play to be irrelevant. Through the years, we’ve updated the play. We mentioned Ukraine in the play since the annexation of Crimea in 2014. The last time we performed it, we added Syria. We added Aleppo to the list of fallen cities, and we will probably add Mariupol for this production. In performing this around the world, we always go into a community and add a significant war for the culture. For us Americans, it’s Vietnam or the Gulf War or the Civil War. In Paris, we added the Battle of Alesia. In Chile, we added a war called 8th November.

KL: You last performed An Iliad in France just before the COVID-19 pandemic erupted in 2020. Plague is another source of strife in the Trojan War. How has our experience of the pandemic changed how you approach this play?

DO: One section discusses Apollo infecting soldiers with plague. Without even trying, lines like “be the plague,” will hit the audience differently. It’s a bit of a tangent, but I was performing Major Barbara on Broadway with Cherry Jones and David Warner in 2001. So this is a play about arms and who has the right for weapons of mass destruction. And the play says everybody does. If you make them, you can’t control them. That’s what the play says. It’s Shaw and it’s a comedy, and it was a comedy up until 9/11, and then we had to play for another week afterward. We canceled several shows, but when we came back, it was so fraught. The words were all the same. But it was so dangerous to do this play now. David Warner had to give a curtain speech [before the performance] because his character would say these really incendiary things. He implored the audience “bear in mind this play is writing about peace. Just listen to it.” And when we came to those scenes, what before had been light and rollicking felt so dangerous and passionate that I as a character had to fight for all it was worth. To paint him as a villain because he represented an idea that the audience was going to hate. The audience will bring their understanding to it. They will bring the context.

KL: What do you hope audiences will walk away with after seeing An Iliad?

DO: That war is a waste. My point of view is that if you took all the money spent on killing people and just gave it to people, it would turn out better. Give them a job. Give them a house. Give them a universal income instead of buying weapons and trying to kill them. The odd idea of war is that just soldiers die, that civilians don’t get killed. But that’s not true. Part of what the play is saying is, look how insane this is.

One always wishes for revelation or deeper understanding. Maybe the experience of seeing the play births an activist. Maybe somebody has a change of heart. But in reality, we can’t control the effect. What the audience brings to that performance will be reflected and carried with them. But given that, it’s hard to sit there and not be stunned by the horror of war.

KL: So on a happy thought, what are you looking forward to most at Spoleto? Have you ever been to Charleston?

DO: I have not been, so I am looking forward to discovering the city. I love history, so I can geek out on historical Charleston. I’m looking forward to hearing some music, seeing other works of art. When we performed An Iliad at the Adelaide Festival, there was an Israeli dance company that shared dinner with us, and all the artists got to mix. It was one of the best experiences of my life. My little son was three at the time and started dancing with this Israeli company. It was just a great atmosphere. I relish the opportunity to meet other artists.